What is the “Rotterdam”? by Ben Boult

Find out more about the dams that held the Castle Pool of Newcastle-under-Lyme in place.

What is the “Rotterdam”? by Ben Boult

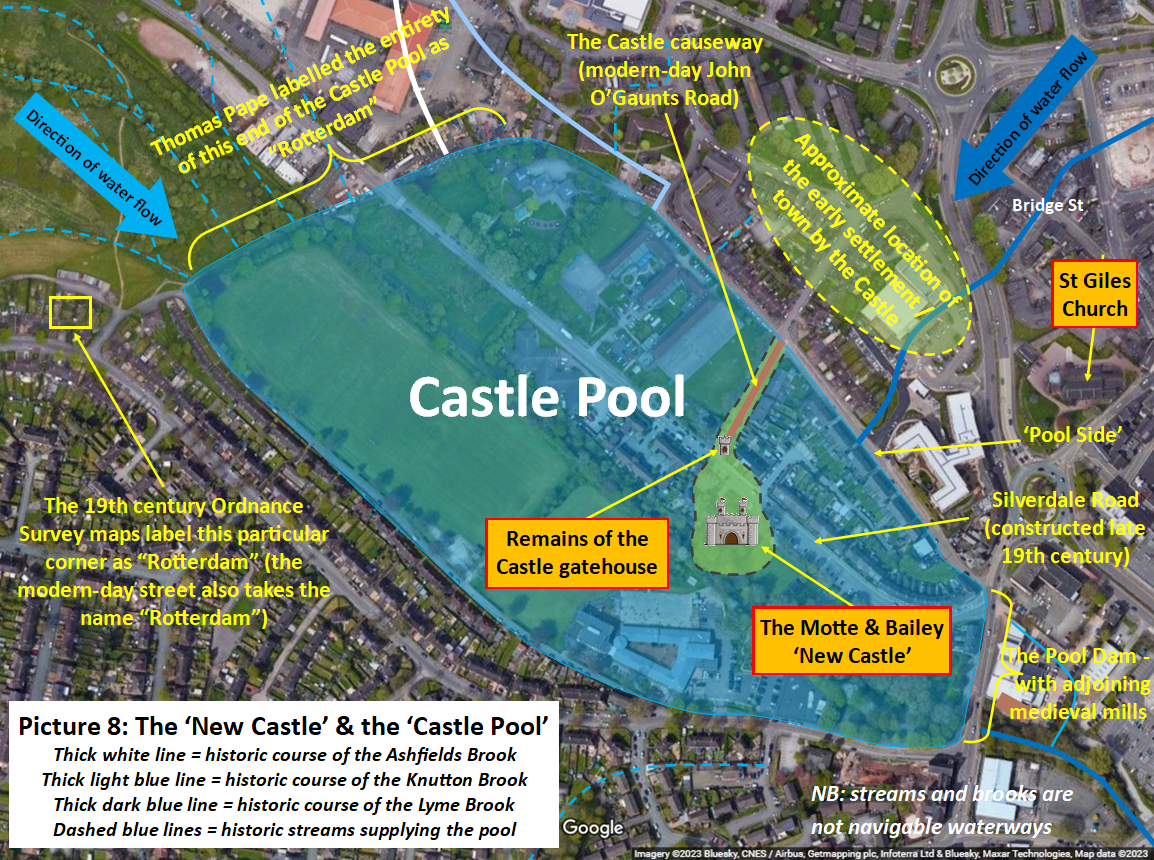

The ‘New Castle’ after which our borough takes its name remains an enigma. We have a general idea of what it looked like - a castle ‘keep’ (or tower) sat atop a ‘motte’ (or high mound), below which there was an oval-shaped ‘bailey’ (or lower mound) containing the kitchen, storerooms and living quarters for the garrison stationed there. At the far end of the bailey stood a gatehouse, which lead onto a wooden causeway. The causeway crossed a defensive body of water known as the Castle Pool.

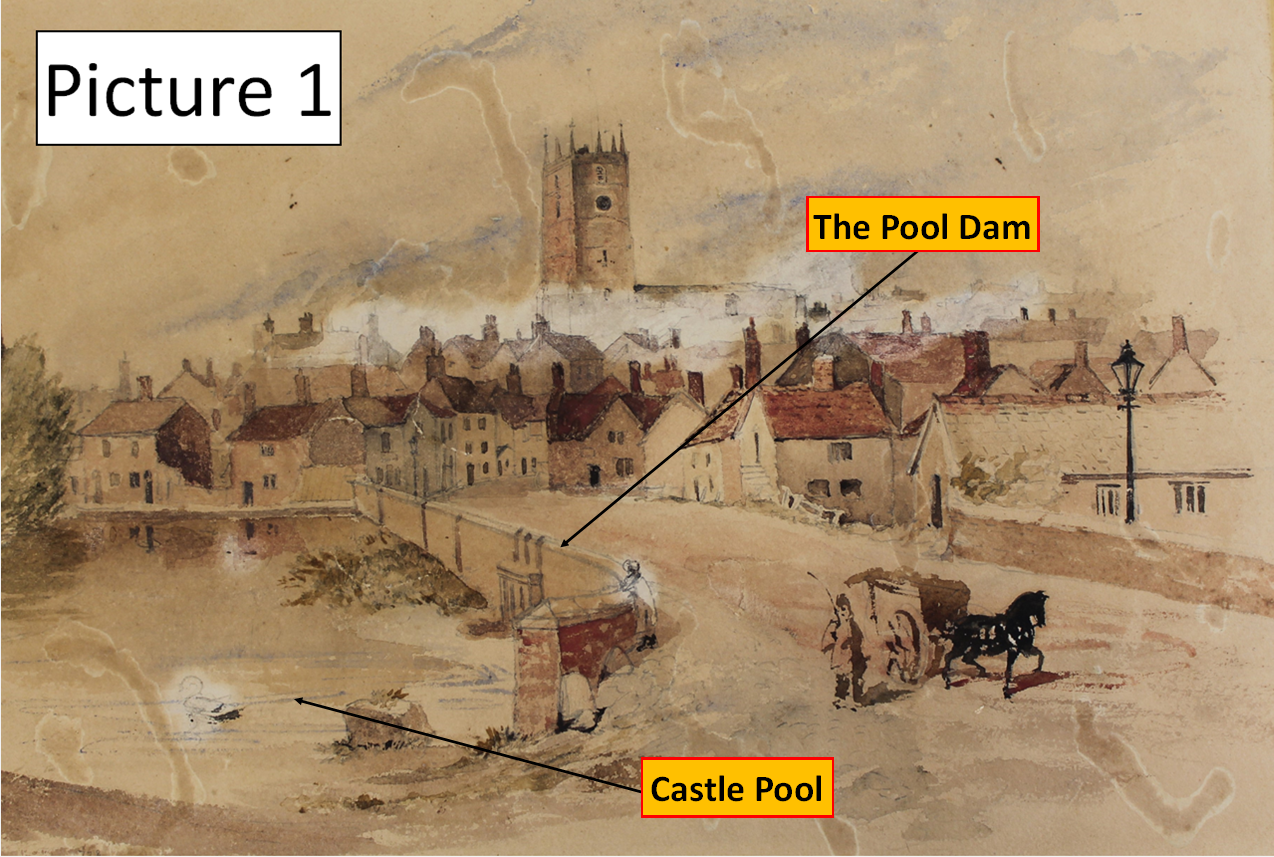

At the eastern-end of the Castle Pool, a man-made dam was constructed to hold the Pool in place. This dam would come to be known as the Pool Dam. Mills were also built alongside the dam to take advantage of the water pressure generated by the pool. We have a rough idea of what the medieval Pool Dam looked like thanks to an 1844 painting by Robert Buss (see picture 1).

We also have an early 20th century photograph taken by Thomas Pape (see picture 2) which gives us a greater sense of the scale of the dam.

But at the Rotterdam end of the Castle Pool, the picture is far less clear…

Firstly, what kind of dam was the Rotterdam? There are no historic paintings or photographs of the dam. Nor are there any physical remains. Save for the place-name “Rotterdam” marked on several historic maps, the idea of a 'dam' at this end of the Pool probably wouldn’t spring to mind…

Secondly, where exactly was the Rotterdam located? Historic ordinance survey maps label one particular corner of Pool Dam playing fields as "Rotterdam" (see picture 3).

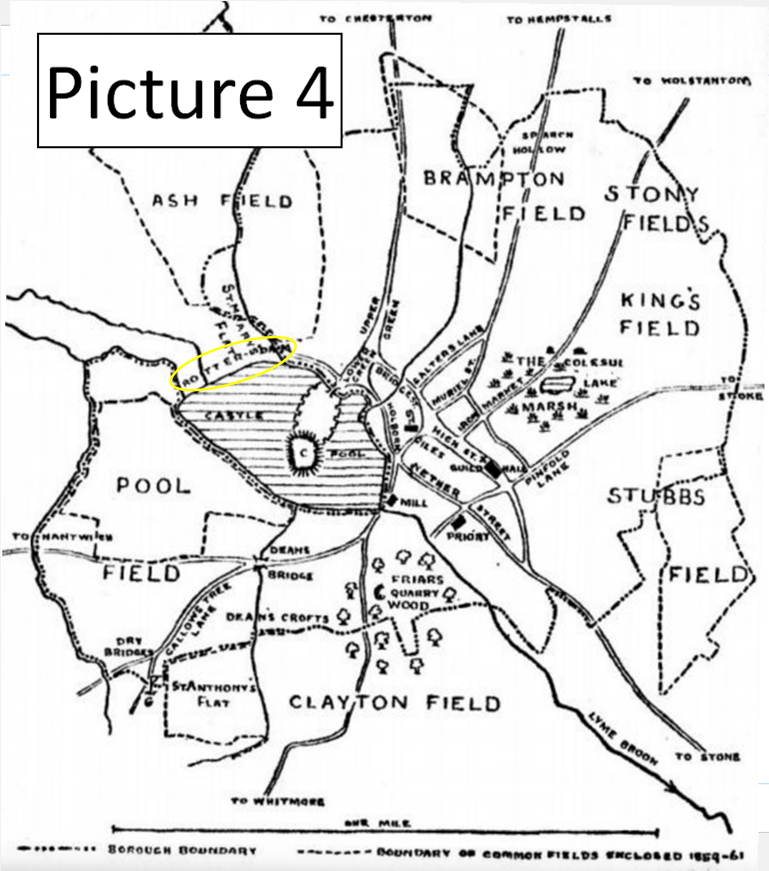

Thomas Pape, an early 20th century historian, went a little further than the OS maps and labelled the entire north-western end of the playing fields as “Rotterdam” (see picture 4).

So if there is no physical evidence of a dam at the Rotterdam end of the Castle Pool, what hope do we have of understanding how it looked / worked? Well thankfully, a quick glance at ‘the lay of the land’ can tell us a lot…

Firstly, we know that the Rotterdam end of the Castle pool was (and is) the higher ground. Looking at the historic maps, it is clear that several streams (including the Ashfields Brook) converged at the Rotterdam end, flowing into the Pool basin to keep it supplied with water.

The ‘direction of water flow’ already tells us something significant about the nature of our dam.

If we imagine the construction of a stone-lined, high-walled ‘dam’ at the Rotterdam end of the Pool – a dam standing in the way of the water flowing into the Castle Pool - this would have had the effect of creating a second pool of water behind the dam. What on earth would be the point of two pools, side by side, one slightly higher than the other? As all of the historic maps of the Castle Pool depict one large, uninterrupted pool, it is clear that the “Rotterdam” wasn’t a conventional stone-lined, high walled dam…

So if it wasn’t a conventional dam, what type of dam was it? There are three possibilities:

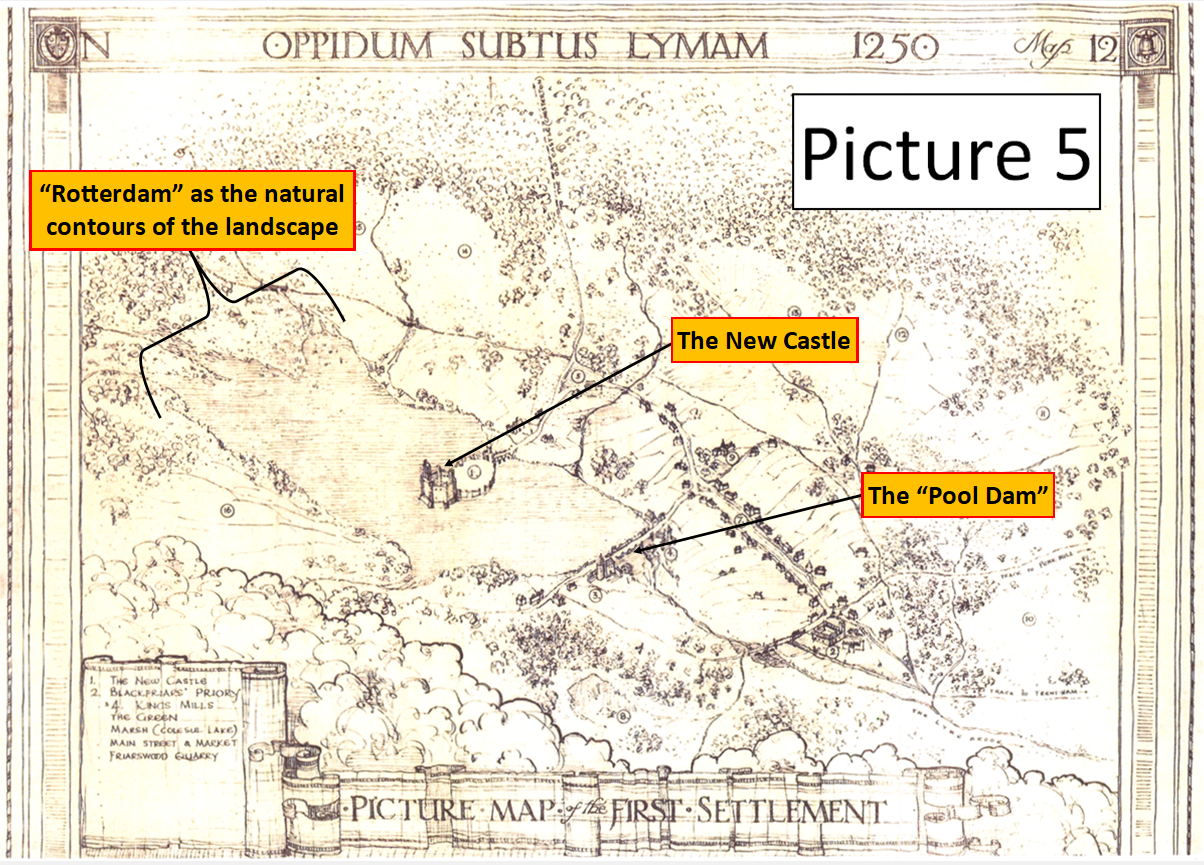

1) A dam forged by the natural contours of the landscape

The “Rotterdam” may have been the point at which the hills of Rotterdam and the Higherland naturally came together to lock in the western-end of the Castle Pool. In other words, the Rotterdam may have been an entirely natural feature, a reference to the contours of the landscape and nothing more. By way of illustration, please see picture 5 which we suspect is a recent interpretation (made to look old) of what a ‘natural’ Rotterdam may have looked like. We’re unsure of the artist / source for this image, so if you have that information, please get in touch!

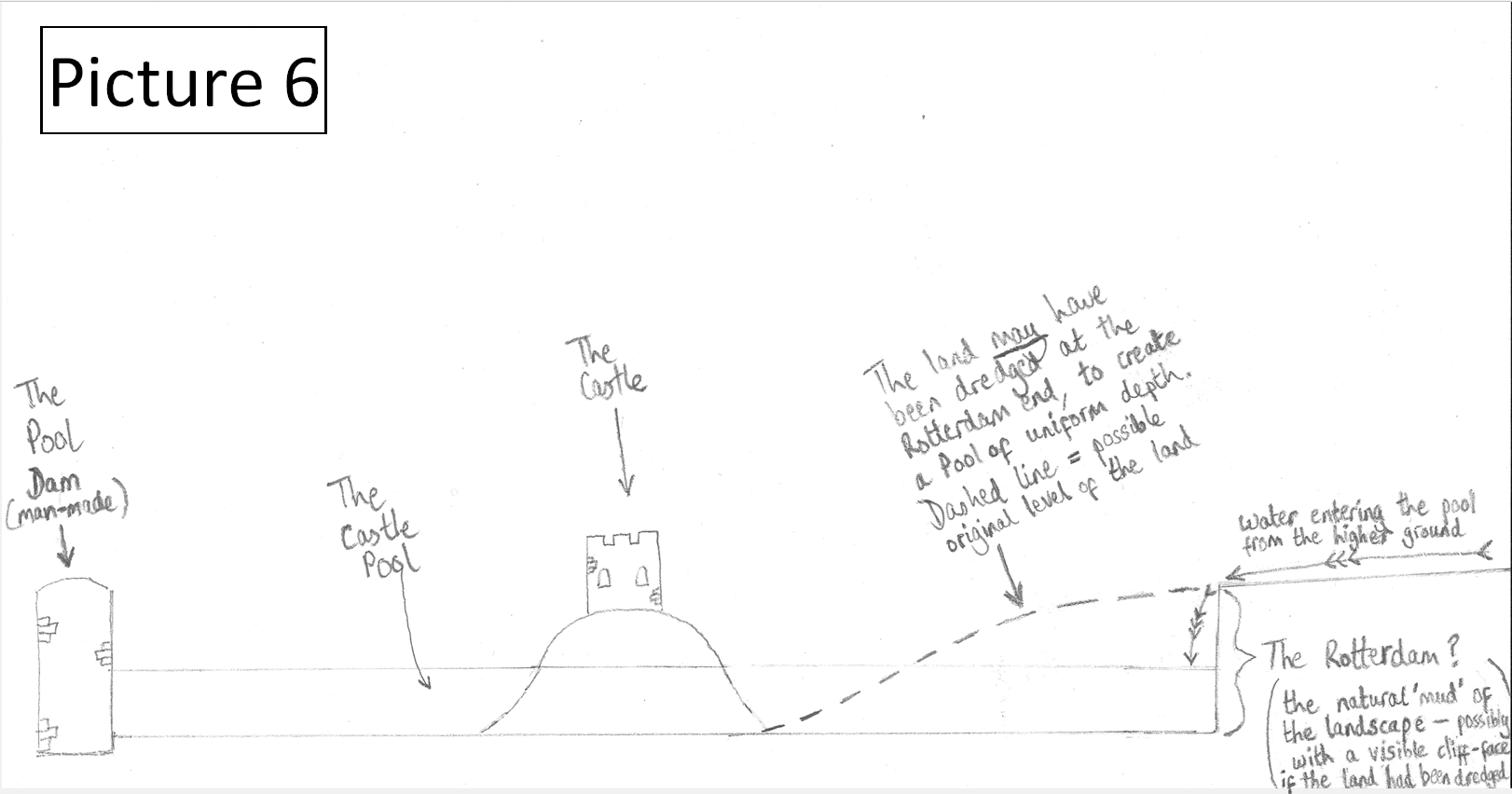

2) A dam formed by the natural contours of the landscape – but with man-made enhancements

If the natural contours of the landscape had been dredged at the Rotterdam end, in order to create a Castle Pool of uniform depth and width, the Ashfields Brook may have trickled into the Castle Pool over a muddy cliff-edge. This cliff-edge, and the cliff-face below it, may have become known locally as the “Rotterdam” (see picture 6).

There are written records which could be interpreted as supporting the idea of dredging works at the Rotterdam end. We know for instance that in 1171 alone, an outlay of £37 (almost £30,000 in today’s money) was spent on maintaining the Pool – with a further £6 spent on a bridge. Writing in the Victoria County History, J G Jenkins argues that “…it is not fanciful to conclude that the pool was being constructed or substantially reconstructed during that time”.

3) A sluice gate / spillway

Thomas Pape argued in his book ‘Medieval Newcastle-under-Lyme’ that the Rotterdam would have had a “regulatory function” – i.e. to stop the Castle Pool from overflowing. A wooden sluice gate, to channel the water away from the Castle Pool, would have made a certain amount of sense. And the fact that one particular corner of the 1847 map (again, see picture 3) is labelled as “Rotterdam” is suggestive of a sluice gate. But one has to wonder - how practical would a sluice gate have been at this end of the Castle Pool? If the builders of the Castle had constructed a sluice gate at the Rotterdam end, they would have had to cut a channel to the carry the excess water from the Ashfields Brook all the way around the Castle Pool, all the way around the Pool Dam and its mills, to the Lyme Brook beyond. Surely it would have been simpler to build a sluice gate into the wall of “The Pool Dam” itself - i.e. at the opposite end of the Castle Pool? By draining excess water at the Pool Dam end, only a small channel would have been needed to redirect the excess water further downstream. In short, Pape’s theory is not entirely persuasive…

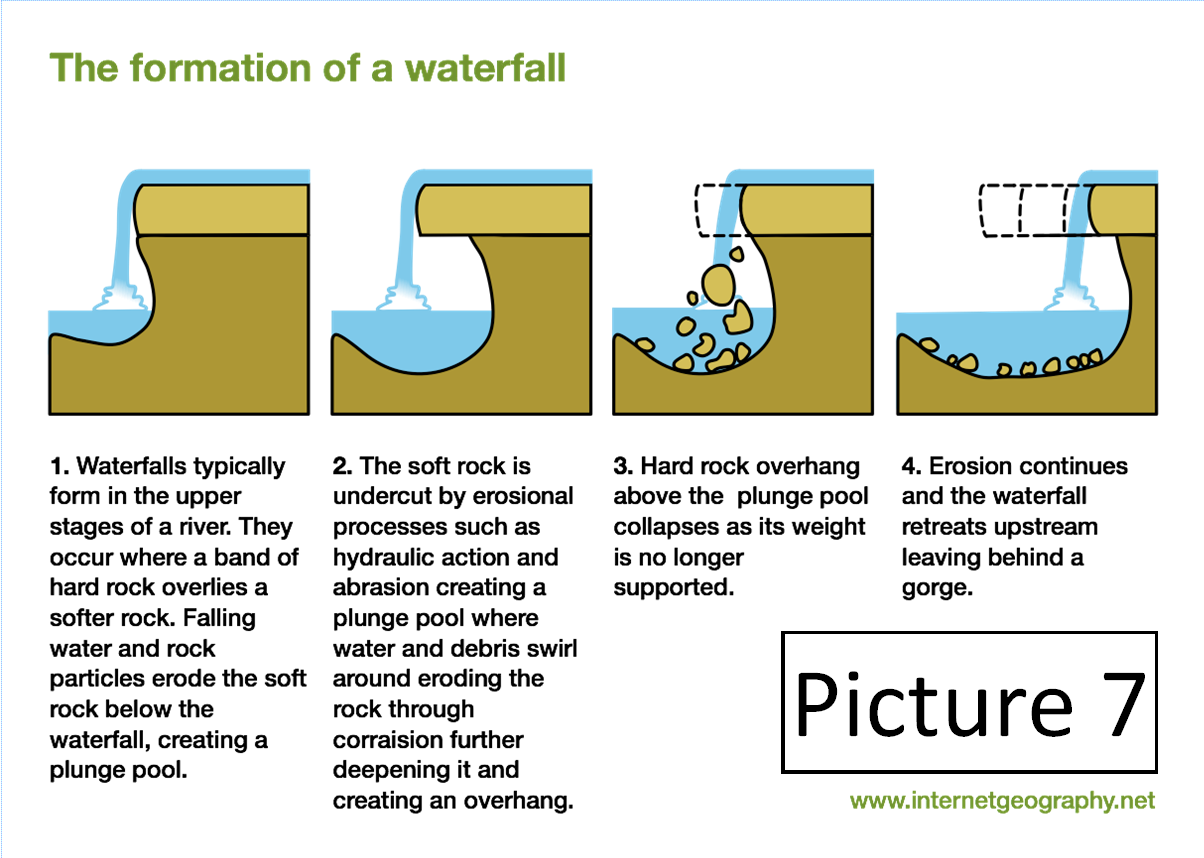

It’s also worth bearing in mind that the landscape of Rotterdam has changed considerably over the last 900 years. Many of those changes can be traced to the levelling works of the 1840s in order to make way for the Silverdale to Newcastle-under-Lyme mineral railway (what would later become known as the “Pool Dam branch”). But an even larger proportion of blame can be attributed to the significant silting / erosive processes associated with continual water-flow over the centuries. Simply put, the silt carried into the Castle Pool by various local streams would have caused the bed of the Pool to rise over time. Likewise, the unending flow of water into the Pool may have pushed the Rotterdam end of the site further and further back (see pictures 7 and 8).

So as we can be fairly certain that the ‘dam’ was a largely - possibly entirely - natural feature, what about its name? Where did the “Rotter” part come from? Well its namesake in the Netherlands might be a good place to start….

The origin of the Dutch name “Rotterdam” is “Rot-a-dam”. “Rot” means “dirty / muddy” and “a” means watercourse (as it does in many European languages). Taken together, this gives you “Dirty watercourse dam”, or to put it more eloquently, “Dam of the dirty watercourse”. We know that our own Castle Pool was very silty / muddy. We also know that the Castle Pool had significant problems with pollution towards the end of its life (the condition of the Pool was flagged as a contributing factor to the cholera outbreak of 1848). Perhaps the Pool was always a little stagnant, with the “Rotter” part of the name reflecting those conditions?

But if the whole of the Castle Pool was stagnant, why did only one side / corner of the Pool come to bear the name “Rotterdam”? The latter observation has led me to conclude that the “Rotter” part is more likely to be a reference to the western-bank itself – i.e. the muddy, weed-filled contours over which the Ashfields Brook and other streams flowed into the Castle Pool.

A “Rotting Dam”, if you will.

We may never know the answer, but it’s certainly fun to speculate! Do you have a theory? If so, please share it in the comments section…

By Ben Boult

References:

1) Overflow from pool at Pool Dam by Thomas Pape [ref no 2064]

Reproduced by kind permission of Keele University Library Special Collections and Archives.

2) A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 8, ed. J G Jenkins (London, 1963), British History Online.

Edit: Picture 8 updated 6.9.2025 to provide greater accuracy

Ben, I've always wondered about the name so really enjoyed reading this article.

Fascinating read Ben, thanks

When was the old Pool Dam taken down and are there any remains

Fascinating! Ive been researching the New Castle and Heighley castle for many years now in order to illustrate how they would of looked and this has added to my info. Thanks Ben.

Very interesting article. Is there anything left of the Rotterdam cottages or farm

Great post Ben and very interesting

Very interesting indeed

so good to hear about this area

Really interesting and well explained. Thanks!