Uncovering the Hidden Story of Staffordshire’s Black Victorians

A behind the scenes look at some of the local history research we've been doing with PHD student Gabriella Gay and how it inspired a living history event.

When did you think the first written record of a black person was in the borough of Newcastle-under Lyme?

You’d probably think 1960s following the arrival of the Windrush, or if earlier perhaps a solider over for one of the World Wars. It’s actually much further back than that. It’s 1677, the time when Charles II and the Stuart family were on the throne.

The man was John Mills and we know his name because he was elected Church Warden of Wolstanton Parish church back in 1677. We also know he was black, due to a million to one fluke. There were two men in the parish called John Mills, so to distinguish between them, the records show it was John Mills ‘the black man’ who was elected.

It’s this sort of chance encounter in the archives that makes you wonder whether there were more Afro-Caribbean and black people living in historic Newcastle that we previously thought, and what their hidden stories might be.

This was the mission local PHD student Gabriella Gay set herself, working with Staffordshire Archives to uncover the Black Presence in Staffordshire. Gabriella remembers her first research visit to Brampton Museum, exploring the Newcastle archives with collections officer Clare Griffiths. During a break she went for an explore around the museum, and spotted something unexpected. Next thing we knew, she was dashing back to reception, excitedly asking for more details about an old photograph on display in the Victorian parlour. The one showing a woman of mixed race.

We were all taken aback. I had walked past this photograph many times but never looked closely enough. I’d never noticed that the woman second from the right on the front row had a different bone structure. Possibly a slight hint of a darker skin tone underneath the sepia. Gabriella was keen to know the history of the photograph, where it was taken and who the women were. As is so often the case with these tantalising survivors from the past, we simply don’t know.

On the back of the photograph was written that it was taken in Hartshill around 1895 and showed ‘women in service, wearing their best clothes.’ The fixed expressions are likely due to the long exposure time needed to take an early photograph. It was virtually impossible to hold a fixed smile without the image blurring. We only know one women’s name, Edith Ward, 2nd from the left on the back row, as the photograph was donated to the museum by her grandniece.

There were so many unanswered questions, one of the keenest being was this photograph a rare incident, a one off? Could there be similar photographs hidden in the archives of museum’s and photography studios across the country? If so, it could overturn the traditional story of what life was like in Victorian England. Gabriella was determined to find out.

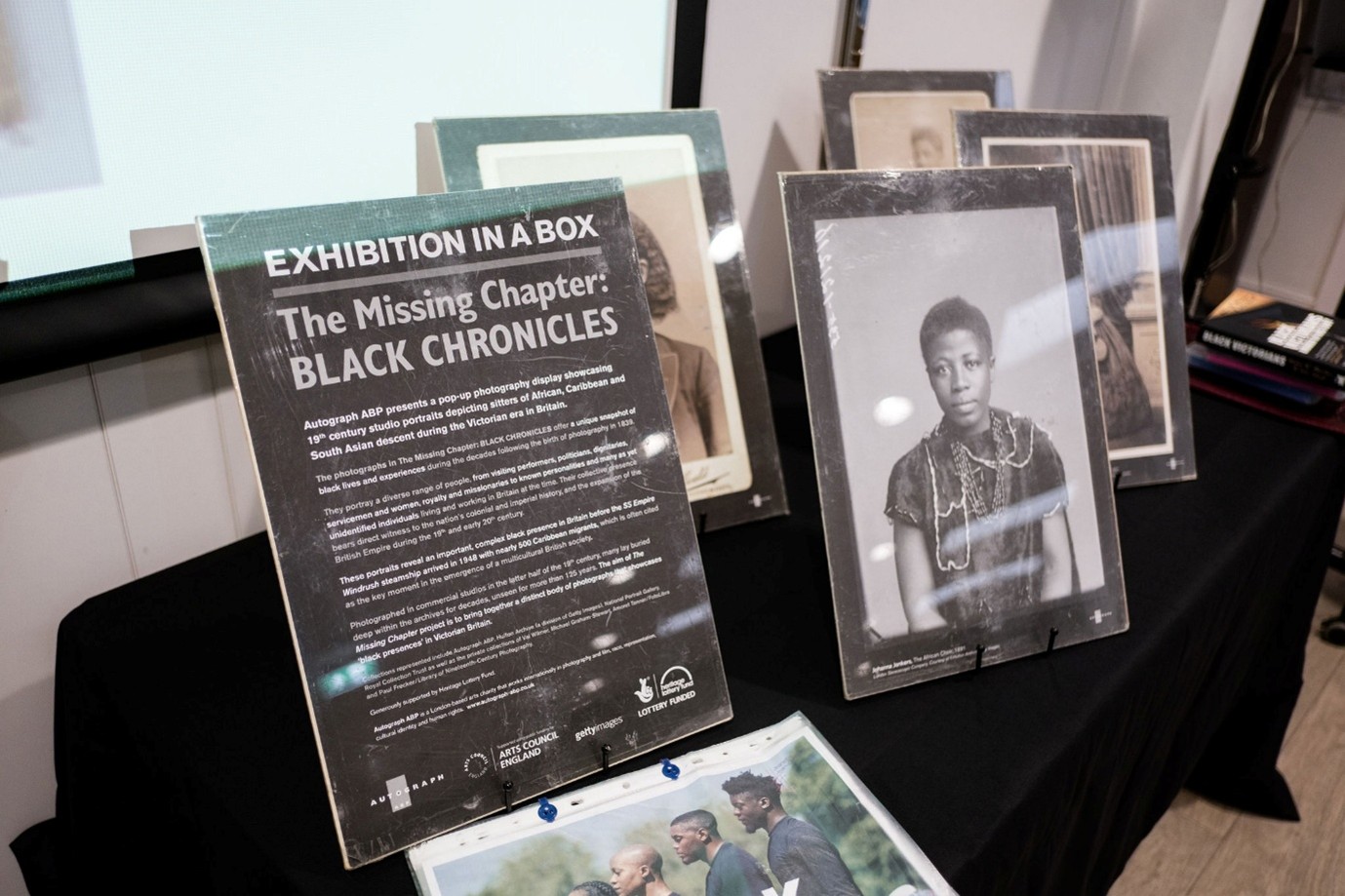

In September 2025, Gabriella and local black artist collective Kwanzaa staged a special living history event at Brampton Museum, titled “Black Victorians.” Featured was not just the photograph from Hartshill, but dozens from archives across the UK, showing people of Black, Caribbean and Asian descent being photographed in professional Victorian studios.

Alongside this, Gabriella shared her latest research. Who knew there was a circus juggler who moved from Madras to Mow Cop and ended up working at Biddulph Colliery?

She was joined by world class choreographer Jeanefer Jean-Charles MBE and her dancers, who reflected on how these photographs inspired the creation of her iconic dance performance “Black Victorians.” (This is available to watch on BBC I-player as part of Dance Passion Swansea, start at 29 minutes).

Jeanefer said “I looked at the images, and thought these are images of Black and Asian people which I didn’t realise existed… Whenever we talk about black history in Britain, we either talk about slavery or the Windrush and there’s no in between, as though we never existed. So when I saw these portraits and realised that there were black people here in the1800s, it really was important to me that that story was told.”

The whole of the museum was transformed that day, with art classes, films and costumed characters strolling around the Victorian street scene. Visitors could even dress up and have their photograph taken in the Victorian parlour.

The photograph that started it all, “Women in Service, Hartshill” still remains on display in the Victorian parlour, waiting until the next chance encounter unlocks the next chapter in its story.

By Elise Turner, Museum Development Officer

The Victorian Parlour within Brampton Museum is open Tuesday-Saturday 10am-5pm and Sunday 1.30pm-5pm, with occasional closures on Tuesday and Wednesday during term time for school visits. If you have any information about this photograph, or any of the others in our online collection, do get in touch at bramptonmuseum@newcastle-staffs.gov.uk

All events described were funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.